Why Rendering a Triangle is Complicated

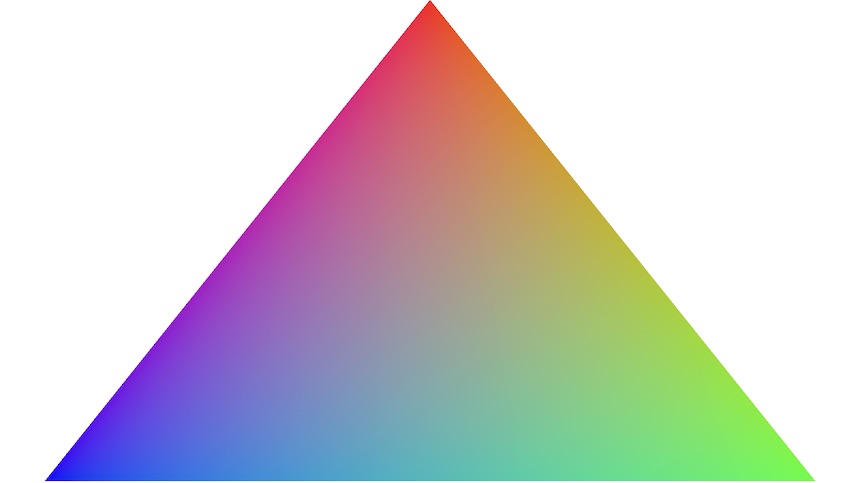

Last week, my dad was asking me why I was proud of this triangle on

my laptop.

I told him that rendering a triangle is complicated: it took me 3

days, and 1000+ lines of code to create the above image. This just made

him more confused.

So I wrote this article explaining what the Vulkan graphics API is,

how it works, and everything that goes into rendering a triangle with

your GPU.

What Vulkan Is

Vulkan is a graphics API that is designed to provide an accurate

abstraction of how modern graphics processing units (GPUs) work. Unlike

OpenGL, Vulkan is very verbose. Every detail related to the graphics API

needs to be set up from scratch. The upsides to this are that you only

use what you choose to, and you can better understand what's going on in

your application and in doing so achieve much higher performance.

This article is intended to be a concise overview of the fundamentals

of Vulkan. It was written for somebody who knew Vulkan but has forgotten

many of the details (i.e. future me). Most of the information here comes

from the Vulkan

1.2 Spec.

Note: This article uses the C++ bindings for

Vulkan

Vulkan in a Nutshell

From a bird's eye view, here's how a Vulkan application

works:

Vulkan can access devices, which let you control one

or more queues. Queues are how you send a list of

commands to the GPU, and they can be members of one or more

queue families, each of which can do different things

(e.g. draw the vertices of a 3D model).

Command buffers are how you submit commands to a

queue. Device commands are 'recorded' to a command buffer through Vulkan

API calls, and can then be submitted once or many times (e.g. once every

frame) to a queue to be executed.

That's the TL;DR - now it's time to dive into the details!

Genesis

Instances and Devices

In the beginning there was the Vulkan API. And the API was made

flesh through vk::Instance, and from it sprung all

per-application state.

You initialize Vulkan by creating an instance, which contains

application state - information like what version of the Vulkan API

you're using, your application's name, and which extensions and layers

you want to enable. Extensions and layers provide behavior that isn't

included by default in Vulkan, like extended error checking and call

logging.

With an instance you can examine the physical

devices (usually GPUs) that are available. A machine might have

multiple physical devices, and each of their properties (such as being a

dedicated graphics card) can be inspected.

A common pattern for physical device selection is to:

- List all of the physical devices

- Score each physical device on desired properties

- Give physical devices without required properties a score of 0

- Pick the physical device with the highest score

Example code for physical device selection

(Tip: Read the comments so you don't get overwhelmed by code)

void pickPhysicalDevice() {

// Get list of all physical devices that can be found by Vulkan

auto physicalDevices = instance.enumeratePhysicalDevices();

if (physicalDevices.size() == 0) {

throw std::runtime_error("No GPUs with Vulkan support found!");

}

// Create list of physical devices sorted by rateDeviceSuitability

std::multimap<int, vk::PhysicalDevice> candidates;

for (const auto& physicalDevice : physicalDevices) {

int score = rateDeviceSuitability(physicalDevice);

candidates.insert(std::make_pair(score, physicalDevice));

}

// Check if best candidate meets required properties (score > 0)

if (candidates.rbegin()->first > 0) {

physicalDevice = candidates.rbegin()->second;

} else {

throw std::runtime_error("failed to find a suitable GPU!");

}

}

int rateDeviceSuitability(vk::PhysicalDevice physicalDevice) {

// Get all features / properties of a given physical device

vk::PhysicalDeviceFeatures deviceFeatures

= physicalDevice.getFeatures();

vk::PhysicalDeviceProperties deviceProperties

= physicalDevice.getProperties();

int score = 0;

if ( deviceProperties.deviceType

== vk::PhysicalDeviceType::eDiscreteGpu)

{

score += 1000; // Prefer dedicated GPUs

}

if (!deviceFeatures.geometryShader) {

return 0; // Require geometry shaders

}

return score;

}

With a physical device you can create a logical

device.

A logical device is basically a physical device (which represents a

GPU) that is initialized and ready for work. They're what you use to

create resources and queues.

Making Stuff Happen

Queues, Command Buffers, and Render

Passes

A queue is a list of commands that the GPU executes.

Each queue can only have certain types of commands (some can have

multiple types, others just one), and this is specified when a queue is

created.

The four types of queue operations are:

- Graphics ---> Drawing the vertices of a

model

- Compute ---> Ray tracing, cloth simulation

- Transfer ---> Loading textures and buffers

- Sparse ---> Loading part of a

'mega-texture'

A physical device will give you access to several queues of different

queue families, and when you create a queue it will be

an index to a queue of a matching queue family on the device. Queue

families are queues that have the same properties as one another (e.g.

perform both graphics and compute operations).

Commands are submitted to queues by first recording a series of

commands into a command buffer and then submitting the entire command

buffer to a queue with vk::Queue::submit().

Note: Command buffers are usually re-recorded every frame (and not

reused) to account for the change in workload in an application (e.g.

drawing a new 3D model after an event).

Also, you can submit multiple command buffers to a single queue. This

is useful because it can allow you to ensure that one set of

commands from a command buffer completes execution before another

command buffer in the queue starts (more on this later), and it allows

you to take advantage of multi-core CPUs by recording each of the

command buffers in parallel on multiple threads.

Finally, commands recorded in command buffers can perform:

- Actions ---> draw, dispatch, clear, copy, query

operations etc

- State setting ---> bind pipelines / buffers,

push constants etc

- Synchronization ---> set / wait events, pipeline

barriers etc

Some commands perform just one of these tasks, while others do

several. A render pass is needed to execute certain

commands, including drawing.

Render Passes

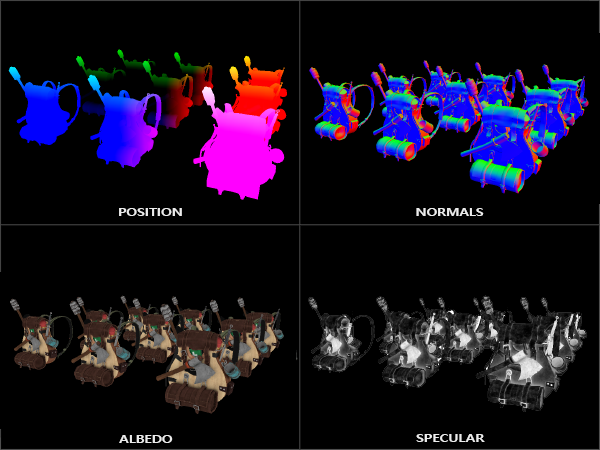

A render pass consists of one or more subpasses,

along with several framebuffers. Framebuffers represent

a series of memory attachments (e.g. color, depth etc) that each subpass

can read from and write to.

A command in a subpass might write to a color buffer, which will

allow for later subpasses / render passes to read from it. This allows

for techniques like deferred rendering.

Deferred rendering is a story for another day, but the gist of it is

that you can store most of the geometry information in an initial render

pass, and defer expensive rendering operations like lighting

for later.

Example code for recording to a command buffer and render pass

// Create a command buffer

vk::CommandBuffer cmd;

// Start recording to the command buffer and render pass

cmd.begin(vk::CommandBufferBeginInfo());

cmd.beginRenderPass(vk::RenderPassBeginInfo());

// Bind a graphics pipeline (covered later)

cmd.bindPipeline(vk::PipelineBindPoint::eGraphics, graphicsPipeline);

// Bind vertex buffers containing info needed to draw vertices

cmd.bindVertexBuffers(0, 1, vertexBuffers, offsets);

// Draw the buffer currently bound to this command buffer

cmd.draw(vertices.size(), 1, 0, 0);

// Stop recording to the render pass and command buffer

cmd.endRenderPass();

cmd.end();

Last thing! Some commands that perform actions (e.g. draw vertices)

do so based on the current state (e.g. the currently bound array of

vertices) set by commands since the start of the command buffer. This

means that in the above code example, cmd.draw() will

operate on the current state set by cmd.bindVertex() in the

previous line. This "synchronization guarantee", that one command will

finish executing before the next one starts, is usually not true.

Synchronization

GPUs are optimized for operation throughput, and because of this

(with a few exceptions) commands are not executed in the

order they were recorded in. The first command that

performs an action in a command buffer isn't guaranteed to finish

executing before the last action command in that buffer. The first

command buffer submitted to a queue won't necessarily finish any

commands before a later command buffer starts. The same thing applies to

command buffers submitted on different queues and multiple

subpasses.

At places the Vulkan spec is confusing on this topic, but the TL;DR

is that this is true unless a synchronization object is

used (or with state setting commands within a single command

buffer).

There are a few different types of synchronization objects:

Fences (GPU to CPU sync) ---> EX: ensure

there are only two rendered frames at a time in the swap chain (i.e.

double buffering)

Semaphores (GPU to GPU sync across queues)

---> EX: wait for frame to finish rendering before presenting

it

Barriers (Sync within a command buffer /

pipeline) --> EX: start compute shader execution as soon as the

vertex shader is finished

Subpass Dependencies (Sync between subpasses)

--> EX: wait for the normal and albedo attachments to complete before

starting the lighting rendering subpass.

Synchronization is closely tied to the graphics

pipeline.

The Graphics Pipeline

The graphics pipeline is what takes the meshes and textures of 3D

models (along with other information) and turns them into pixels on your

2D screen. Each stage of the graphics pipeline operates on the output of

the previous stage.

There are two types of stages in the graphics pipeline:

fixed-functions and shaders.

Fixed-functions complete operations that can be

tweaked with parameters, but the way they work is predefined. Anything

in the graphics pipeline that isn't a shader is a fixed function.

Shaders are user-created programs that execute in

the graphics pipeline. They can read from input variables (e.g. position

of vertex / fragment / light) and run on GPUs, which are great at

parallel computing tasks such as applying the same lighting rule for

every one of the 2 million pixels on your screen or rotating a 3D model

with thousands of vertices.

A simplified overview of the graphics pipeline consists of 7

stages:

Input Assembler: Collects the raw vertex data

from specified buffers. Optionally, an index buffer can be used to

repeat certain elements without duplicating vertex data.

Vertex Shader: Runs on every vertex and passes

per-vertex data down the graphics pipeline. Usually applies

transformations to vertices, and converts from model space to screen

space.

Tessellation: Optional. Runs on arrays of

vertices ("patches") and subdivides them into smaller

primitives.

Geometry Shader: Optional. Runs on every

primitive (triangle, line, point) and can discard or output more

primitives. This stage is often not used because its performance isn't

great on most graphics cards.

Rasterization: Discretizes the primitives into

fragments (the data necessary to generate a pixel). Fragments that fall

outside the screen and fragments that are behind other primitives are

discarded.

Fragment Shader: Runs on every fragment and

determines its color, depth value, and which framebuffer the fragment is

written to. Often uses interpolated data from the vertex shader such as

surface normals to apply lighting.

Color Blending: Applies operations to mix

different fragments that map to the same pixel in the framebuffer.

Fragments can overwrite each other, or be mixed based on

transparency.

Shader Modules

Unlike OpenGL, shader code in Vulkan has to be in a bytecode format

called SPIR-V, as opposed to human-readable syntax like GLSL.

The advantage of using a bytecode format is that the compilers to

turn shader code into native GPU code are significantly less complex.

This leads to SPIR-V shader code being more reliable across GPU

vendors.

However, shaders are still commonly written in GLSL, and later

compiled to SPIR-V using a tool called glslc (included in

the Vulkan SDK). SPIR-V can be passed to the graphics pipeline by

reading the bytecode, and then wrapping it in a

vk::ShaderModule object, which specifies the entry point

function in the shader, and assigning it to a specific stage of the

graphics.

Presentation Time

Swap Chains and Window Surfaces

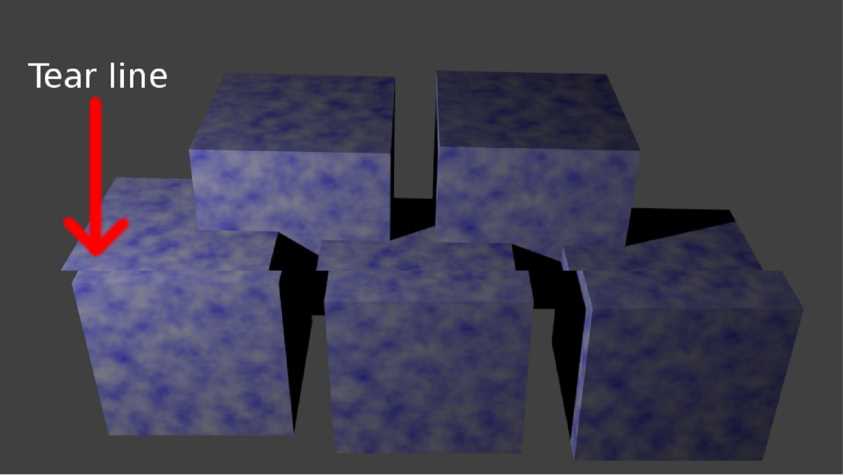

We've done all of this work to render an image, now we need to

present that image to a window surface from the

swap chain.

A window surface allows you to interact with platform specific

display systems.

A swap chain is an array of at least two presentable images. The

first image is the screenbuffer, which is the image presented to the

screen, and later images are backbuffers. If you don't use a backbuffer

and directly send new images to the screenbuffer, image tearing (where

the top portion of the screen contains the new image and the bottom

portion contains the old image) will occur while the monitor is

refreshing.

Using a screenbuffer and a single backbuffer is known as a double

buffer. This technique prevents image tearing.

Rendering a Triangle

To bring it all together, in a Vulkan application:

We start by creating an instance, a physical device, and a

logical device.

Commands are recorded in command buffers and render passes, which

are submitted to queues. The GPU goes through the queues and executes

the commands in them

To guarantee that certain commands occur after other commands

finish executing, synchronization objects have to be used.

Some commands are involved with stages in the graphics pipeline,

which can either be shaders or fixed functions, and turns 3D data into a

2D image

Finally, the window surface presents images from a swap chain to

the screen

That's why rendering a triangle is complicated.

Feel free to contact me on Twitter. Feedback and

comments are appreciated :)